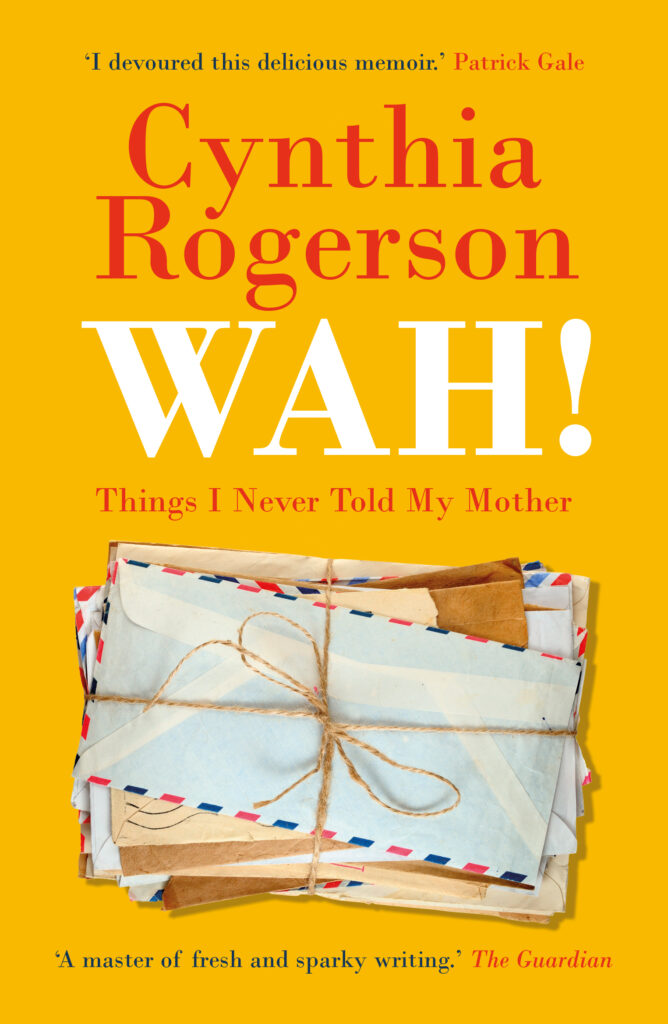

Cynthia’s mother is dying.

Often.

Travelling between her home in Scotland and California, as she spends time at her mother’s bedside Cynthia recalls her youthful adventures: living in a squat, train-hopping, hitchhiking and all the other things she never told her mother.

Wonderfully witty and refreshingly candid, Wah! is an unflinching look at life in all its uncertain and messy glory.

Sandstone Press, 2022

Cynthia Rogerson (aka Addison Jones) grew up in California. She is the author of six novels and a collection of short stories. She won the V.S.Pritchett Prize in 2008, and her short stories have been widely broadcast and anthologised. I Love You Goodbye was shortlisted for Best Scottish Novel in 2011 and translated into five languages. She holds a Royal Literary Fund Fellowship.

You can read a short extract from the book below

Extract from WAH! Things I Never Told My Mother

The following excerpt is published with permission from Cynthia Rogerson and Sandstone Press and should not be downloaded, distributed, or reproduced in any way.

The summer my mother started dying in earnest, it stopped raining in Scotland. Our well ran dry and we took showers at my daughter’s house. Wildfires broke out and no one knew what to do. All this distracted me from my mother’s impending death in San Rafael, California – but it also seemed to emphasise it. Like her dying, it was both shocking and natural. What did we expect? Most people on the planet had already suffered because of climate change, but it was hard not to take personally. Tempting to see the drought as a result of Mom dying, as if in her death throes, her panic was drying up clouds. Or maybe the heat wave was California coming to me at last, summoned by decades of homesickness. Maybe it had missed me too, sought me everywhere till it finally found me hiding in the Scottish Highlands. I was tired and tended to read meaning into everything.

My first deathbed visit was in August.

‘The end, it is here. You must come,’ said her caregiver on the phone.

Ateca was a Fijian woman, 64 years old, and whenever she told me to do something, I did it. Her voice was gruff and staccato. When she watched football on television, she sat hunched forward, legs apart, and shouted like a man. Run, run, run, you beauty! Or more often: No, no, no! What’s the matter with you?

I arrived to find my mother in a hospital bed next to her own bed. My sister explained that’s what hospice means in California. Hospice comes to you.

‘Mom, I’m here!’

‘How did you get here?’

‘Flew.’

‘You flew!? What do you mean?’

‘I flew in an airplane to come and see you.’

‘That is…charming!’

It turned out that at the end, not only did you lose your independence, you didn’t even get to pick your own words. You just got what you got. My mother got charming, delightful, creepy, correct and wah. She used wah a lot, by itself, with a capital letter and an exclamation mark. Basically her Wah! meant I have no fucking idea what to say. It was never said without a smile, so I think there was also an element of defiance. I have no fucking idea what to say and I don’t give a shit. She never swore, but that didn’t mean she didn’t think in swears.

She didn’t learn any Fijian words, even though she heard Ateca on the phone all day. Not even bula. All of Ateca’s conversations began and ended with bula-bula. Every time I heard that, an old Motown song would start up in my head. I didn’t know which one, but that didn’t matter. She’s my baby, bula-bula, bula-bula, bula-bula.

I lowered my face to Mom’s hospital bed and kissed her. She gave me three hard kisses back. She smelled of Clinique night cream and looked pretty. Somehow, she’d skipped the unattractive side of old age and leapfrogged straight into the home run.

‘See you in the morning, Mom. Goodnight.’

‘God bless you,’ she said, which was odd because we were the kind of Catholics who got embarrassed when people talked about God. Maybe Ateca, who was Pentecostal, had rubbed off on her.

It must have been confusing for my mother to see her own bed but not be in it. Or maybe sometimes she did see her old self in her old life, wearing that Lanz nightgown with the top button missing. Her husband not dead, but snoring next to her, making that loud popping noise like a rubber ball bouncing down the street.

‘Hey, it’s me,’ she might have whispered to herself. ‘Wake up. You won’t believe what’s going to happen to you.’

But then her own words would waken her, and she’d just be her old lady self in a hospital bed looking at her empty marital bed. She might notice it was much more neatly made than she’d ever managed and think: Wah!

The next day, when I popped into her bedroom to say good morning, her face lit up as if she hadn’t seen me for a hundred years. Her famous red-lipstick smile, her teeth miraculously still white, still straight.

‘Is it really you? All the way from Scotland?’

‘Yup,’ I said, feeling goofily happy.

‘Come here, you.’ She stretched her arms out towards me and we hugged.

Oh, I was going to miss this kind of appreciation. My mother loved me more than anyone loved me, even my father who’d set out to woo me and in large part succeeded. She loved me more than I loved her. I never loved my mother enough to tell her what was really going on in my life. In the early years, sometimes months went by when I didn’t even bother sending a postcard. I used to tell myself I was protecting her, but the truth was less noble. I was a daddy’s girl and kept her at a distance. I probably made my mother cry sometimes. Made the person who loved me more than anyone else in the world loved me, cry. So perhaps it wasn’t ironic that at her deathbed I had an urge to record the truth of my past. As if the child who’d been careless with her abundance of motherly love was now insisting – stamping her feet! – on making up for lost time. Memories lurked everywhere I looked – had been lurking for decades – but they lurked no longer. They stepped into the light and said in a slightly patronising voice: Yeah, you really did this and said that dumb thing, right here, in this exact spot.

I sat at my dead father’s desk, opened my laptop and began to write. I began with my father throwing his glass of wine at me because I’d had sex with the boy down the street who he’d expressly forbidden me to see. Had I really been that stupid? That bad? And then I remembered moving in with a man who lived inside his foam furniture factory. He’d picked me up hitchhiking, which was the main way I met boys in those days. I studied my right thumb, recalling how I wriggled it at the side of the road fifty years ago. I’d loved not knowing which of the passing cars would stop, not knowing where I’d be in an hour. It seemed I could be my truest self with strangers.

Wah, wah, wah! I thought, sick of myself suddenly.

My wah was not my mother’s wah. It was more like the wah in Peanuts, when a grown-up tries to talk but all that Charlie Brown hears is wah-wah-wah. And then, because my mother would soon be gone, I had a silent little sob for myself. Which was, I suppose, another kind of wah.